"Day had turned cold and gray when the man turned aside from the main Yukon trail. He climbed the high earth-bank where a little-traveled trail led east through the pine forest. It was a high bank, and he paused to breathe at the top. He excused the act to himself by looking at his watch. It was nine o’clock in the morning. There was no sun or promise of sun, although there was not a cloud in the sky. It was a clear day. However, there seemed to be an indescribable darkness over the face of things. That was because the sun was absent from the sky. This fact did not worry the man. He was not alarmed by the lack of sun. It had been days since he had seen the sun."

Jack London (1876-1916) was born in San Francisco, near Third and Brannan, mere blocks away from the exhibition hall we used every other year for the California International Antiquarian Book Fair. That book fair has now relocated to Oakland, mere blocks away from Jack London Square. Jack London’s mother, saddled with a newborn (the father is unknown although most think it was the astrologer William Chaney, with whom Jack’s mother had been living), married a partly disabled Civil War veteran named John London, and the family moved to Oakland.

London credited his later literary success to his early years in Oakland, where he attended grade school and where he first learned to love reading, spending much time at the Oakland Public Library, where a sympathetic librarian named Ina Coolbrith mentored him (he later referred to her as his “literary mother”) and guided his book selections. Starting at age twelve or so, Jack also began working, first at Hickmott’s Cannery (which was located at First and Filbert Streets in Oakland), then at a number of odd jobs around town, often under grueling conditions, with low wages and long hours. He quit school, signed on as an oyster pirate and had many teenage experiences as a dock worker, sailor, hobo, and tramp.

Coming back to Oakland, he attended high school, publishing stories and accounts of his adventurous life in the high school literary magazine. He seemed to like to do his studying (and perhaps his drinking) at Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon, located at 48 Webster St. (Jack London Square), a tavern that is still in business. The bartender there lent Jack money to attend college at UC Berkeley. The autobiographical novel John Barleycorn mentions a pub very much like Heinold’s several times.

"The dog followed again at his heels, with its tail hanging low, as

the man started to walk along the frozen stream. The old sled trail could

be seen, but a dozen inches of snow covered the marks of the last sleds.

In a month no man had traveled up or down that silent creek. The man

went steadily ahead. He was not much of a thinker. At that moment he

had nothing to think about except that he would eat lunch at the

stream’s divide and that at six o’clock he would be in camp with the

boys. There was nobody to talk to; and, had there been, speech would

not have been possible because of the ice around his mouth."

Jack started attending Berkeley in 1896, but couldn’t afford the tuition the next year and left college without ever graduating. In 1898 he went up north to join the Klondike Gold Rush, the setting of his two most famous works, The Call of the Wild and White Fang and the setting as well of a number of now famous short stories, including “To Build a Fire” (the passages quoted in this article are from that story).

The power of London’s work and its continued readability derives from a number of factors, the source for each of which can be found in the years he spent in Oakland. First, his prose has an easy fluidity that suggests deep study of the work of other prose stylists, that goes back to his childhood discovery of reading at the local library. In fact, as he became successful, London became quite the book collector, eventually amassing a personal library of over 15,000 volumes that he referred to as “the tools of my trade.” Second, his experiences in the world of blue collar workers and tramps gave him a consciousness of the capitalist exploitation of the workingman, and he left Oakland with clear socialist tendencies that never deserted him. It also endowed his work with a sense of empathy with those whom society has roughly treated, which extends even to the animals and sled dogs that populate his books.

"The dog was sorry to leave and looked toward the fire. This man

did not know cold. Possibly none of his ancestors had known cold, real

cold. But the dog knew and all of its family knew. And it knew that it

was not good to walk outside in such fearful cold. It was the time to lie

in a hole in the snow and to wait for this awful cold to stop. There was

no real bond between the dog and the man. The one was the slave of

the other. The dog made no effort to indicate its fears to the man. It

was not concerned with the well-being of the man. It was for its own

sake that it looked toward the fire. But the man whistled, and spoke to

it with the sound of the whip in his voice. So the dog started walking

close to the man’s heels and followed him along the trail."

And at Heinold’s and among the workers and tramps he learned the language and culture of the pub and the dock, his varied experiences giving his work an authenticity that other authors could not match. Thus, although his work is often slotted into the genre fiction categories of Boy’s Adventure Books or Popular Fiction (as opposed to Literature), he transcends those genres and is more avidly collected and more widely read than those contemporaries of his who were writing in those genres. So, thank you, Oakland, for giving American literature Jack London!

"He should not have built the fire under the pine tree. He should have built it in an open space. But it had been easier to pull the sticks from the bushes and drop them directly on the fire.

Now the tree under which he had done this carried a weight of snow on its branches. No wind had been blowing for weeks and each branch was heavy with snow. Each time he pulled a stick he shook the tree slightly. There had been just enough movement to cause the awful thing to happen. High up in the tree one branch dropped its load of snow. This fell on the branches beneath. This process continued, spreading through the whole tree. The snow fell without warning upon the man and the fire, and the fire was dead. Where it had burned was a pile of fresh snow."

-- "To Build a Fire," Jack London

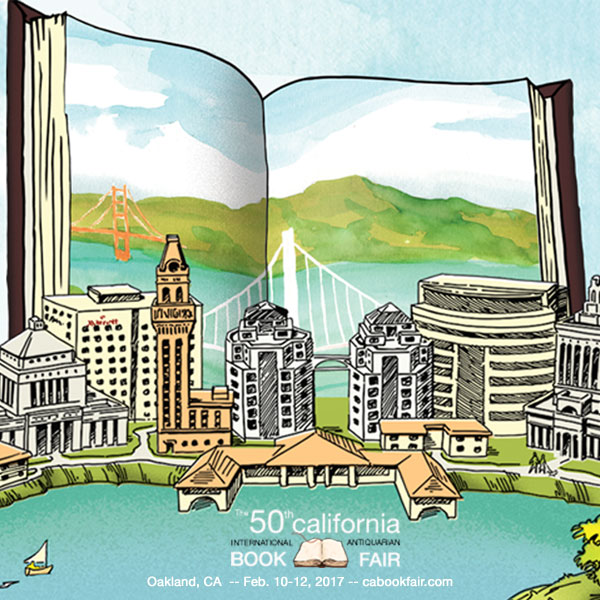

The 50th annual California International Antiquarian Book Fair takes place in Oakland, CA over the weekend of Februrary 10-12, 2017. More info: www.cabookfair.com...